Anglers Benefit as River Management Helps Fish Thrive

Waves lapped the rocks. Ospreys wheeled and chortled overhead. And anglers hooked all kinds of fish off the riverbank in downtown Knoxville.

“I’ve caught skipjack herring, bluegill and yellow perch and smallmouth, white and largemouth bass,” Conservation Fisheries director Bo Baxter said. “It’s a great little spot.”

He and Dave Matthews weren’t casting for just any fish, though.

They sought a relatively rare fish for these parts – a silver chub.

It’s a sturdy little creature that’s appeared out of the blue on anglers’ hooks in the upper reaches of the mainstem Tennessee River.

And that’s a good sign.

“They’re a big river species,” Matthews, Tennessee Valley Authority aquatic zoologist, said. “And they’re hard to collect.”

That so many of these flashy fish are showing up here means they’re thriving in the river, perhaps expanding their range.

And it means the long-term river management that TVA does while generating reliable, affordable hydroelectric power is also helping fish – and those who catch them.

Across the Valley region, TVA works to ensure river health. Its environmental stewardship of the region’s waters and lands improves lives and brings billions of dollars to local economies through recreation and conservation. It also saves billions of dollars through flood control and helps ensure TVA can produce power across the Valley region.

“Going from uncommon to consistently caught angling is really impressive,” Baxter said. “That means that population’s increasing.”

The Tennessee River flowing through downtown Knoxville. (Photos by Susan Ehrenclou / TVA).

Benefits Below Dams

The story of the Tennessee River before TVA was one of extremes.

Severe droughts one year.

Raging floods the next.

And sometimes, the river didn’t run at all.

That left fish and other aquatic creatures high and dry.

While damming the river did change fish migration, TVA sought to help fish thrive.

TVA’s scientists and engineers studied the river to simultaneously produce energy, protect people and help fish.

And they’ve succeeded.

During the 1990s, TVA launched the Reservoir Release Improvement Program – an innovative way to keep rivers below dams flowing consistently and full of oxygen.

Baxter, who grew up fishing the Clinch River below Norris Dam in Tennessee, remembers walking bank to bank on dry shoals.

Everything changed when TVA began managing the reservoirs as part of an interconnected river, rather than a system of lakes.

It made all the difference.

“In my lifetime I’ve really watched this river come back,” Baxter said, gesturing to the Tennessee flowing by. “It’s exciting.”

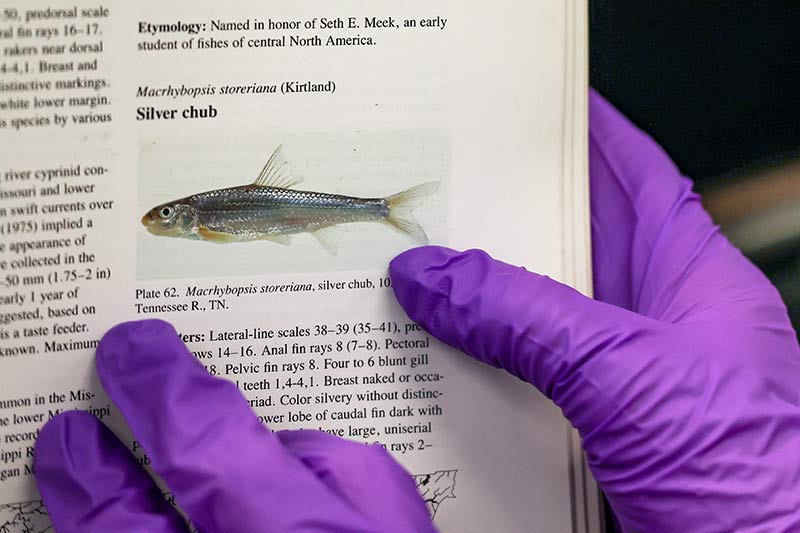

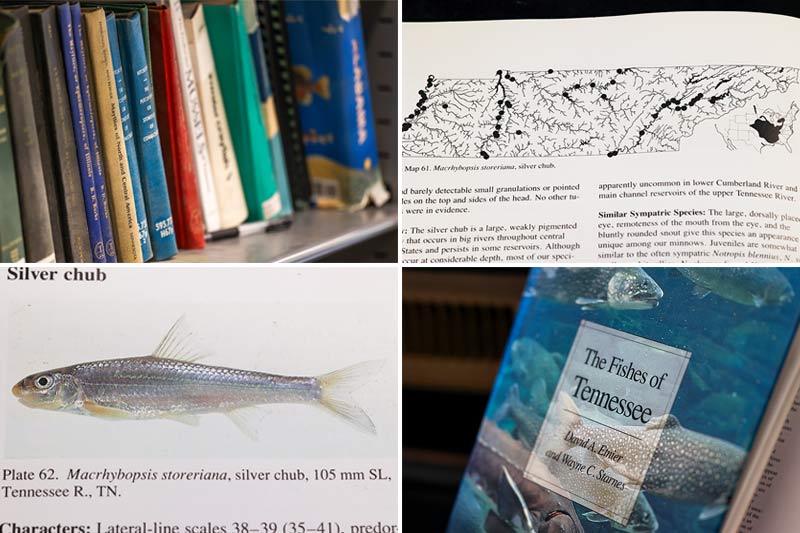

Fish books at the Norris Fisheries and Aquatic Monitoring lab provide useful information about the silver chub.

Fish Power

Understanding the river – and precisely monitoring the flow and oxygen levels at points downstream of dams – is a science that takes teamwork.

TVA’s River Management engineers input data – weather forecasts, the season and shape of the land and how much rain will soak in or run off – into computer models.

They’re responsible for making sure water always flows at a certain rate, come drought or high water, measured in cubic feet per second at gauges downstream.

TVA’s River Operations team adds oxygen at tributary dams, either with liquid oxygen or through new, highly efficient turbines.

All that work creates the right conditions for fish.

Big fish such as sturgeon once again patrol the deep, making long-distance migrations to spawn upriver.

Little fish may do the same, although as both Baxter and Matthews pointed out, many small-bodied fish aren’t yet well-studied.

“Some of these 3-inch fish will travel 20 to 30 miles,” Baxter said. “They’re probably spending most of their time out in the main river and then moving up the tributary streams for spawning.”

He pointed toward First Creek.

It flows into the main river at a spot where Baxter believes silver chub swim or find food during May and June spawning season.

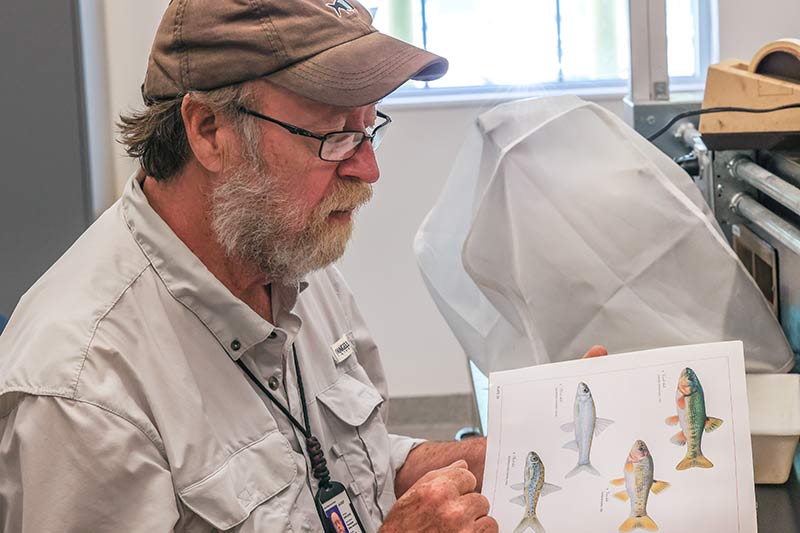

“They’re not really all that common, this whole genus of chubs,” Matthews said. He flipped open a shiny guide, “The Fishes of Tennessee,” by David Etnier and Wayne Starnes.

“‘Common in lower Tennessee, Duck and Mississippi rivers. Persistent but apparently uncommon in lower Cumberland and main channel reservoirs of upper Tennessee,’” he read.

Uncommon – but that’s where anglers had been frequently catching them now, in these upper reaches near Knoxville.

In addition to TVA’s river management, food sources may be another reason silver chub appear to be expanding their range.

They’re not picky eaters.

With low slits for mouths, they nibble plant seeds. Slurp up aquatic insect larvae. Gulp up invasive Asiatic clams and gobble mayflies.

“Those are a big, high-protein source in one meal,” Matthews chuckled.

For all these reasons, the silver chub appears on more anglers’ hooks than ever, in the upper reaches of a river where it’s been rare.

“It’s an indicator species,” Baxter said. “It’s one of the canaries in the coal mine – that’s why we study them.”

Dave Matthews, TVA aquatic zoologist, refers to a fish guide at the Norris Fisheries and Aquatic Monitoring lab.

On the Banks, In the Water

The silver chub’s success has a lot to do with efforts of TVA and its partners on land, too.

Over the decades, limits on chemical pollution made creeks that flow into the Tennessee River cleaner.

TVA’s partnered with city, county and farming organizations on riparian plantings – trees, bushes and no-mow zones along riverbanks – that help stop silt and dirt from washing into the water.

And now many people tackle trash.

A few feet away from where anglers cast lines, a trash boom that Ijams Nature Center monitors stretches across the mouth of First Creek.

Similar booms block trash where Second and Third creeks carry litter from city streets and stormwater drains into the river.

“The boom’s caught a basketball, a foam cooler and a lot of Styrofoam cups,” Baxter said. “Everything ends up in the river. And then the ocean.”

He pointed upriver to a spot around a bend, where the city draws in drinking water.

“And in us, with microplastics,” he said.

Bo Baxter, director and senior conservation biologist at Conservation Fisheries, casts a line in downtown Knoxville.

Future of Fish

Ensuring great fishing opportunities – and more sightings of fish such as the silver chub – is interwoven with TVA’s ability to produce reliable hydroelectric power.

TVA’s operations, river management and aquatic monitoring work in harmony to build a tomorrow where all in the Valley region can enjoy these waters.

“Water is fundamental to life,” Baxter said. “It’s power generation and recreation and flood control. If we keep the ecosystem in mind, then it should meet all those other uses.”

Matthews agreed.

“One of the big mission objectives of TVA was to improve the quality of life in the Tennessee Valley,” Matthews said. “And by having our finger on the pulse of these rivers and how healthy they are, we’re improving the quality of life and knowledge of the Tennessee River. I think that’s very, very important.”

Reeling in his line from the slightest tug, Baxter agreed.

“I’ve seen the improvements TVA’s made, and they’re impressive,” he said. “I’m excited to see what the next 30 years brings – and I’m excited to be on the river.”

Fish books – including “The Fishes of Tennessee,” by David Etnier and Wayne Starnes – are among the trove of resources on hand at the Norris Fisheries and Aquatic Monitoring lab.

Baxter prepares a hook for fishing in downtown Knoxville.